Heaven and Hell in Chefchaouen

Behind the glossy Instagram images lies another side of Chefchaouen...

Chefchaouen. The Blue City. A magical oasis of pristine sapphire stairways and stunning azure lanes. Jasmine and oleander cascade over cerulean walls, a vivid rug of petals scattered across the cornflower cobbles. Ginger and white street cats laze in the cobalt shade, effortlessly pleased with themselves and their perfect accent colours. The smiles of Berber women beam from beneath decorated straw hats and baskets of herbs. Mysterious figures cloaked in woollen burnooses glide through the blue dream world.

At least that’s what it looked like on Instagram. The carefully curated, airbrushed version of this Moroccan mountain town. But what they had failed to capture in all its other-worldly glory was Chefchaouen Bus Station. And its toilet.

If the town itself was painted blue to connect it with Heaven, the Bus Station was resolutely rooted in death’s alternative destination. A silent haze of lethargic flies hovered at head height in the sickly yellow strip-light. In the centre of the grimy concourse lay a bizarre mountain of mail. A paunchy man in a sweat-soaked uniform was yelling at no one in particular and gesturing furiously at the pile of brown envelopes and parcels. A few young men slumped on corroded metal benches, passively watching his performance as they smoked. I tried to hold my breath against the overpowering stench of drains and peered around the terminal hall for a sign. Not necessarily a sign from God, just a vague indication of where the bathroom might be. I had a bad feeling about this place, but with a churning stomach full of ominous flutterings, and a five hour bus journey ahead, a visit to the facilities seemed unavoidable.

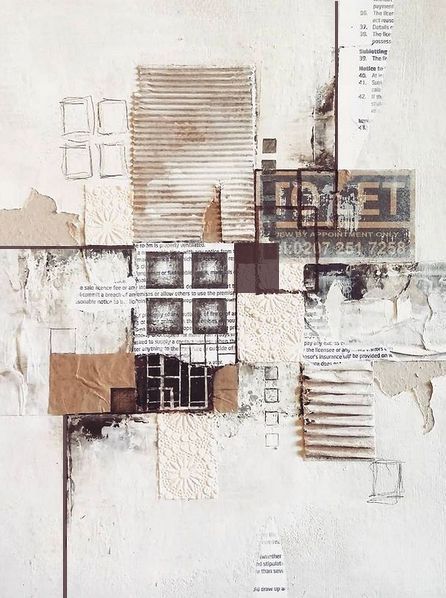

As I exited the terminal building I noticed a tattered piece of cardboard nailed to the wall on which the word ‘toilette’ was scrawled in biro along with a shaky arrow. I followed its lead across the tarmac towards what could loosely be described as a building. The structure’s crumbling walls were topped with a millefeuille of materials from mangled sheets of corrugated iron to ripped plastic sacks and polythene. In front was a scrapheap of broken plastic chairs, refuse bags spewing out their putrid contents and a scowling man slouched on a crate guarding two foreboding doorways. He didn’t look up as I approached, nor when I said ‘excusé moi’. ‘Toilette ici?’ I asked, hoping he’d direct me elsewhere. ‘Deux dirhams,’ he barked, thrusting out a grubby hand. I reluctantly rummaged in my purse and dropped the requested coins into his palm. He gestured dismissively to the dark entrance on the left.

Thankfully I am not a large person. If I were, it would have proved impossible to squeeze myself and my luggage through the tiny passageway. I edged this way and that, stepping around, over and through a junkyard of empty water dispensers, broken buckets and filthy mops. Compared to the stench in here, the aromas of the terminal building now seemed like a fragrance that could be packaged and sold. At least there were cubicles though, even if they were lacking doors. For maximum privacy and comfort I continued to the last stall but recoiled, confused. I retraced a few steps through the clutter, checking the other cubicles, and felt my heart sink into my already churning bowels. Les toilettes did not actually have any toilettes - each stall was equipped with only a hole in the ground, a rusty bucket and a gang of attendant wasps.

However, it was now day 3 of my Tagine Evacuation Mission, therefore there was no time to ponder the various courses of action offered by the hole and the bucket. I moved my luggage back to a place of safety and rapidly relieved myself of several hundred exotic calories. The wasps were joined by a party of unfamiliar scuttling insects, arriving from all directions to investigate the exciting new splatter. I retched, sweating and shivering, as I rummaged through my luggage to find tissues. The empty bucket, caked in what I hoped was rust, was useless without water, so I sloshed the last litre of my drinking water over the cracked ceramic floor towards the hole, and backed out of the stall.

With no sink or running water, hand washing was clearly not included in the two dirhams. The lack of facilities did however allow for a swifter exit. Nothing short of full immersion in a tank of Dettol would make me feel clean now anyway, I thought as I rubbed sanitiser onto my hands and picked my way back through the graveyard of soiled cleaning equipment.

As I emerged into the light I was greeted - or more accurately, accosted - by a different man. Twice the size, twice as dirty and with half the charm of his predecessor, he barred my exit. ‘Excusé moi,’ I said, trying to get past. ‘Cinq dirhams,’ he spat, holding out a shovel-sized hand. ‘Non!’ I cried. ‘I paid already!’ ‘Cinq dirhams,’ he repeated louder, his face now close enough that I could smell his rancid breath. I stared at him long and hard, my gaze boring into his tiny, dark slits of eyes. He was not backing down and, out of the corner of my eye, I could already see passengers boarding the bus for Fes. I sorted through the loose change in my pocket and roughly shoved a five dirham coin into his sweaty hand. He sneered and stepped aside slightly, so I could squeeze past, pressed against his huge filthy bulk.

As I strode towards the waiting coach I reflected that it was probably appropriate that it cost more to leave the toilettes than it cost to enter - the high price of freedom. Suddenly I realised, with a huge sense of regret, that, like every other traveller before me, I too had failed to take a photo of the Chefchaouen Bus Station toilet. Instagram’s vision of Chefchaouen would remain untainted, unspoiled, unblemished. As I sanitised my hands one more time, I wished I could say the same for myself.